The Dali Dimension

/A couple of weeks ago I watched a documentary called The Dali Dimension, which came out in 2005. I had rented the DVD from Netflix hoping it would delve into his methodology, in particular the paranoiac critical method he developed. Instead, the film focusses on Dali's interest in math and science, and his interactions with accomplished scientists throughout his lifetime, which turned out to be really interesting, since I hadn't realized he was so tuned-in to trends in science, and moreover, that this sensibility influenced his works. For example, he had a fascination with psychoanalysis, quantum mechanics and nuclear physics, DNA, and computational geometry. Toward the end of his life, in 1985 an interdisciplinary congress/conference was held at the Teatre-Museu Dali in Figueres, Spain, where many of the mathematicians and scientists he had developed friendships with over the years gathered to discuss their discoveries and ideas. The film uses this event as a sort of lynchpin to tie together biographical footage exploring his various pursuits of scientific understanding.

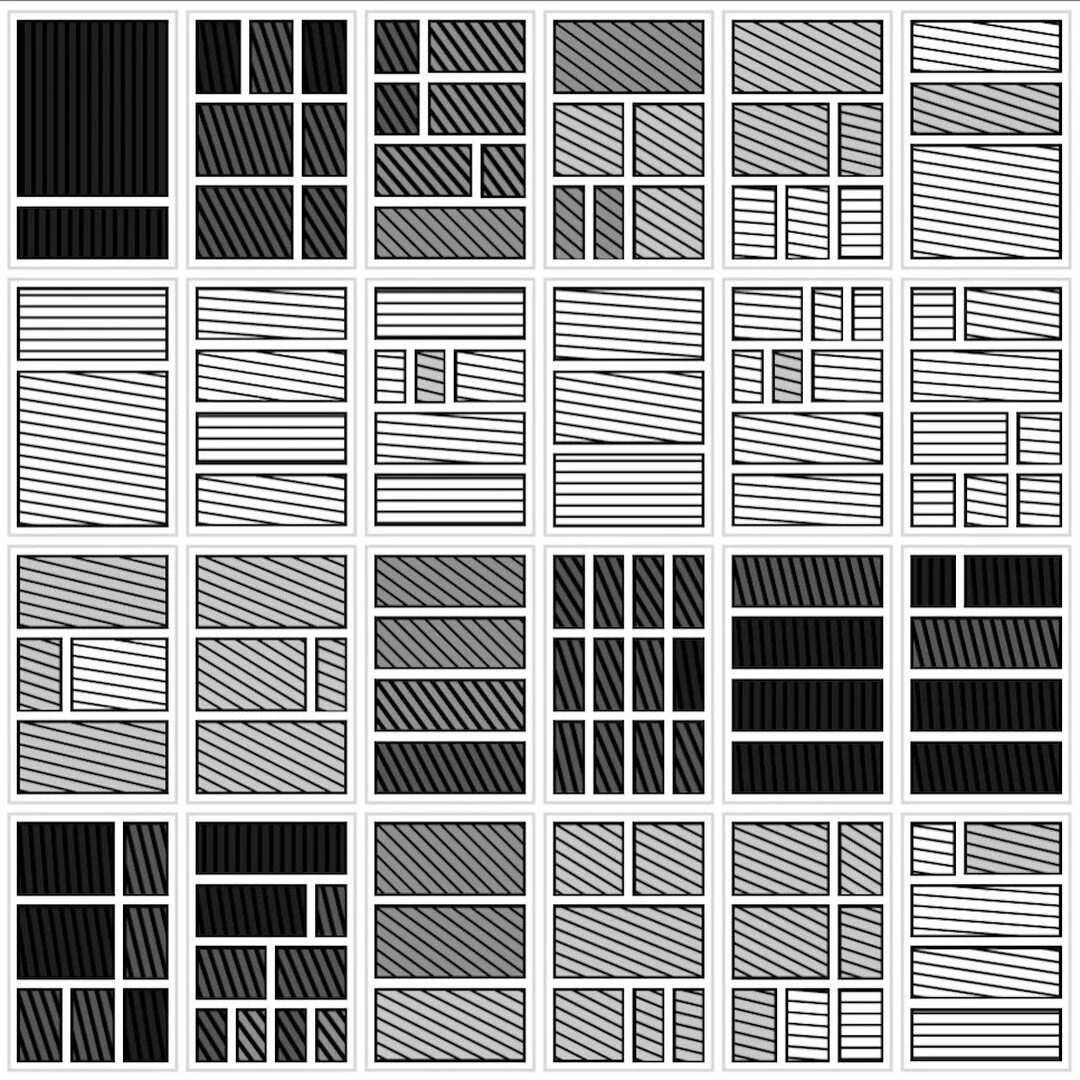

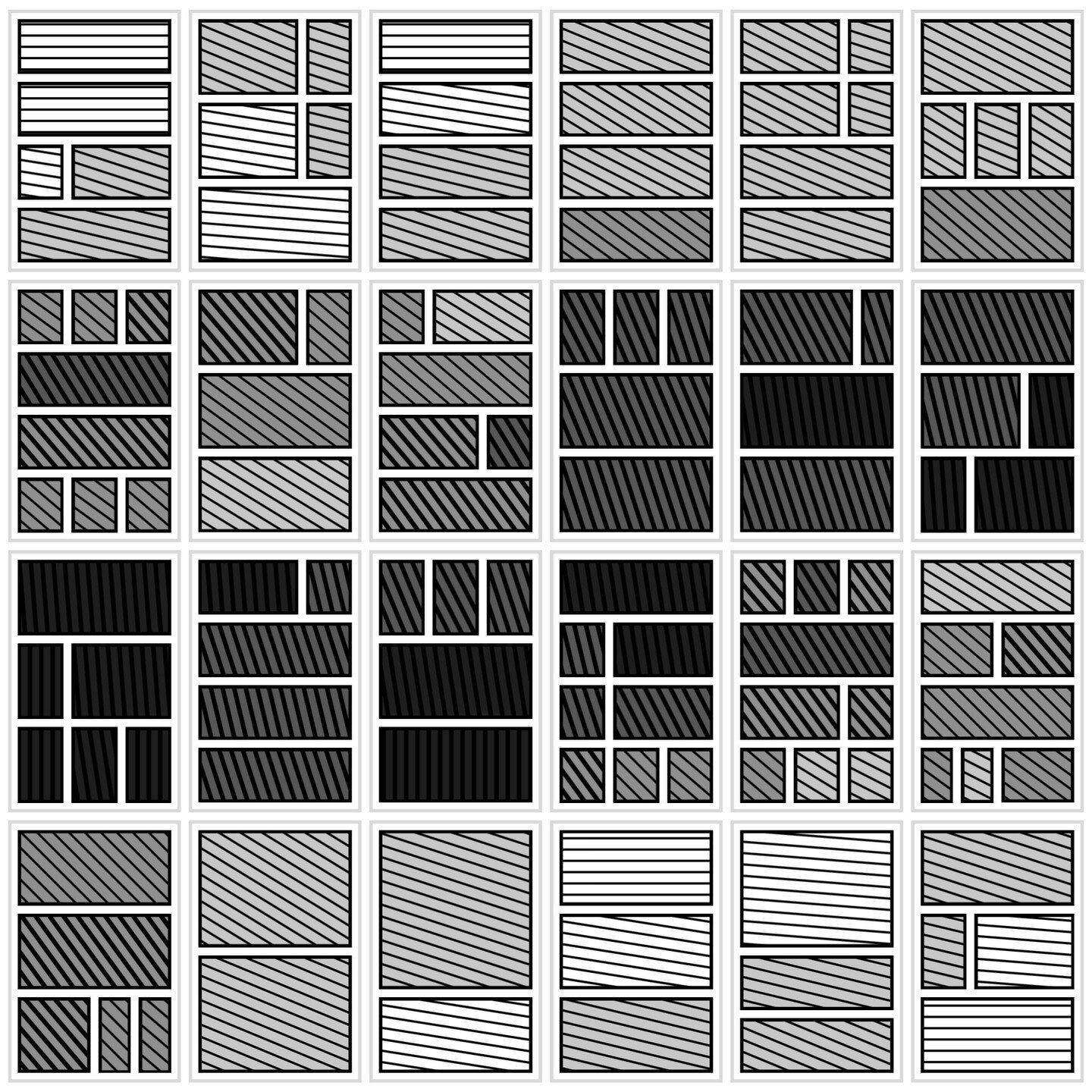

One of the more interesting notions I distilled from the film is that Dali had a tendency toward metacognition-related themes in his paintings. That is, his paintings often invoked symbols or patterns that can project the viewer out into a higher plane of awareness, where one's mind is able to peer in onto itself and sense the interpretive mechanisms at play in one's own cognitive processing. Dali coined the phrase paranoiac critical method to refer to the techniques he employed to induce this sort of metacognitive response. The painting fragment above is a good example of this technique, where the mind's deep-rooted ability to recognize human faces is triggered by the miscellaneous arranged objects in the composition. These explorations remind me of an intriguing book published by O'Reilly called Mind Hacks, which offers a series of cognitive experiments, such as viewing optical illusions, that allow one to sense other-wise unconscious mechanisms being triggered in the brain.

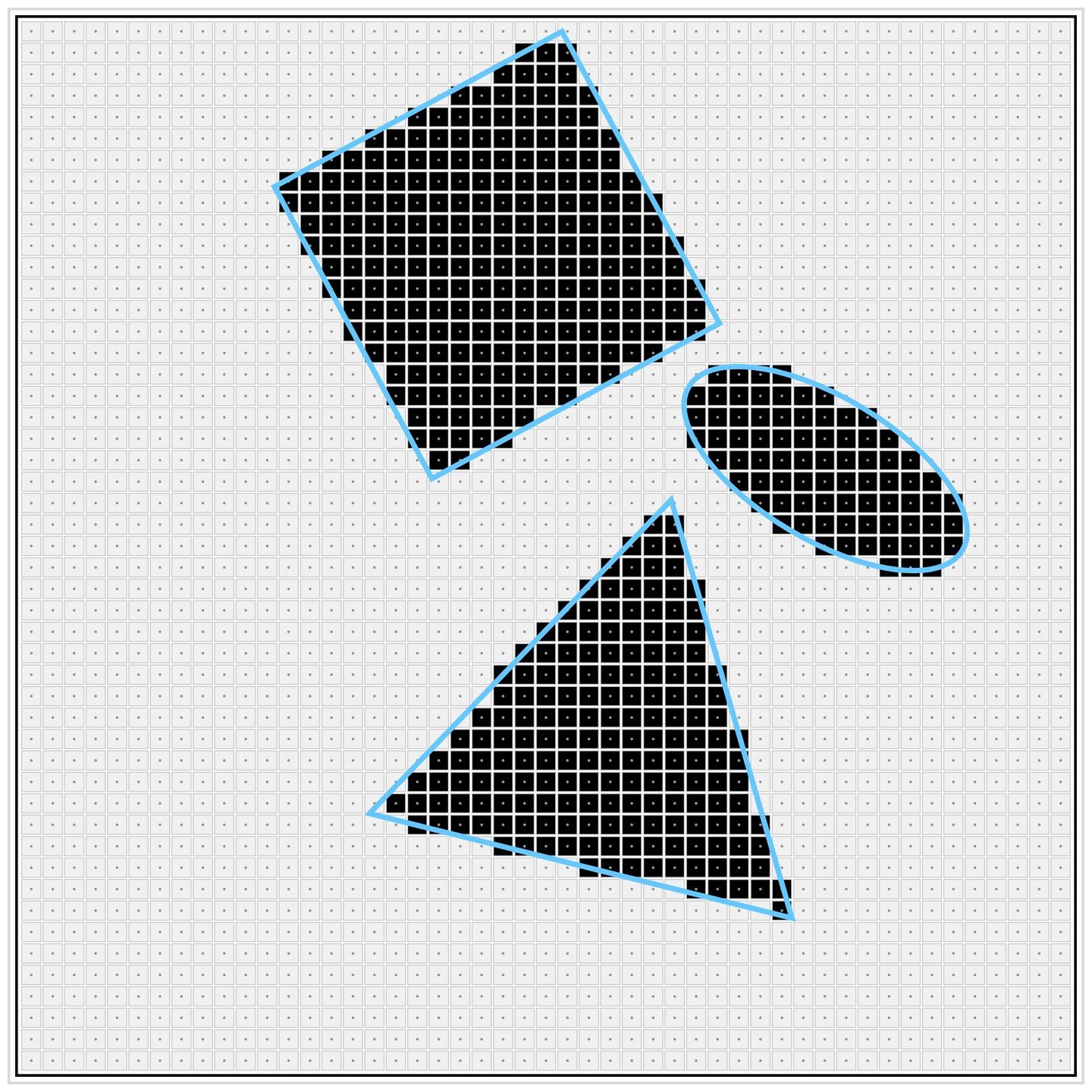

The crescendo of the film occurred toward the end when the religious and scientific underpinnings of his painting The Crucifixion were being explored. The painting depicts Christ being crucified on an unfolded four dimensional hypercube. I don't think I had ever seen this painting before (or if I had it didn't leave an impression). The image of the hypercube represents a kind of meta-awareness or transcendence out of our everyday plane of existence (our perceived three-dimensional world) into another higher-dimensional realm, much in the same fashion that his paranoiac critical method tries to induce. In Western culture, the crucifixion of Christ also represents a transcendence, but a spiritual one. I like this duality at play in the image, which for me symbolizes two distinct ways of understanding our world: from a spiritual/religious perspective and from a rational/scientific perspective. And what I find most intriguing of all is that our tendency to seek out and find patterns in the world, our apophenia-like tendencies if you will, are at play in both religious and scientific thought. So I see a strong connection between this painting and the notions I'm attempting to highlight in the created name of this blog.

The Crucifixion, 1954

The Crucifixion, 1954